Can You Hear Me? Recurring Sonic and Musical Gestures In The Works of David Bowie

I haven't had the time to write this presentation up as a proper paper, all I have here are the slides, audio examples and my own notes. If you're interested in seeing/hearing the ideas from the first of my talks given at the Symposium on the Stardom and Celebrity of David Bowie, held in Melbourne last July, click the 'read more' link below.

Opening:

The music of David Bowie is one of my favourite subjects, one that I feel sometimes gets sidelined (even diminished) in critical discussions about Bowie, particularly when we’re talking about an artist whose contribution to popular culture is so visual, multi-disciplinary and wide reaching. However in focussing on the shared qualities of his musical outputs we can begin to understand that an individually stylised musicianship has been present throughout his long career, to look beyond style changes and genre shifts to the core creative musical voice at the source.

Slide 2:

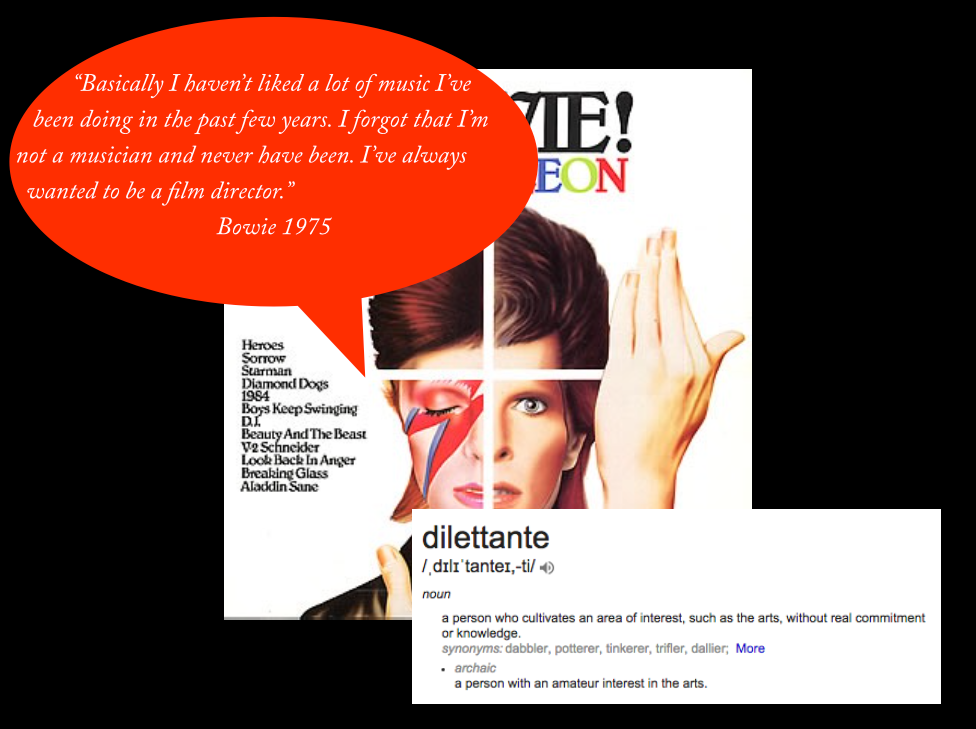

Consider this familiar image: Bowie the always changing chameleon - adopting and abandoning musical styles as quickly as he changes his haircut. Another: Bowie the magpie - stealing and appropriating from pop culture, from other more ‘authentic’ originators. These common images contribute to the sense that Bowie’s music might at times be inauthentic, a secondary consideration to larger theatrical/literary/abstract ideas; that he might be a ‘curator’ of musical ideas and not really a ‘composer’ of them.

It doesn't help matters when Bowie himself claims not to be a musician (refer to quote on slide), similar to a declaration made by ‘non-musician’ Brian Eno, which seems ludicrous in light of the 300+ published compositions and associated arrangements, vocal and instrumental performances and records he has produced across his long career. Perhaps these statements are symptomatic of being a pop musician in the reign of Dylan. Authenticity might be a more flexible idea these days, certainly you don’t see many artists having to defend style evolutions and experimentation like Bowie and Eno had to in the 70s. Of course Bowie cleared the way for many musical artists to feel free to shift, try, experiment and follow their creative curiosity. Further pulling of that thread would need a totally different presentation, however. For this talk I want to focus on a particular area of Bowie’s creative practice.

Slide 3:

David Bowie is… a whole bunch of interesting things. It’s a great PR campaign isn't it? You could argue he’s a myth, a hack, a genius, a chancer, a grafter, a great pair of legs. No matter what you come up with, at the core is an identity as a creative musician. A singer/songwriter who has penned some of the most distinctive, unusual and beautiful pop melodies of the last 50 years. David Bowie is a world class musician engaging in multiple pop music creativities, with a personally developed sonic and musical vernacular.

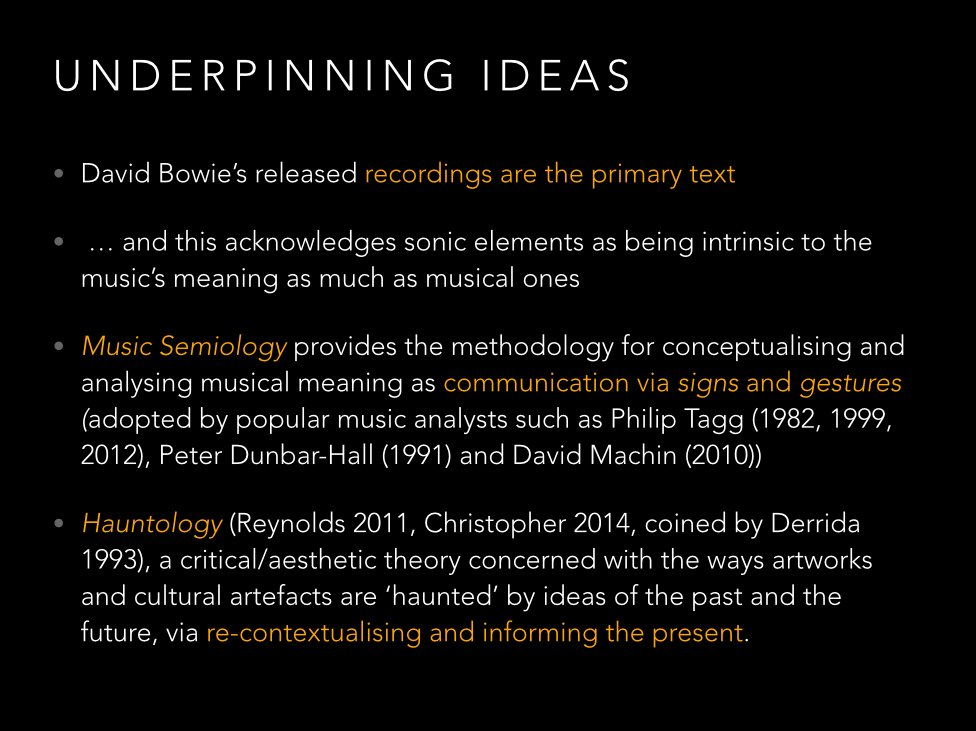

Slide 4:

Before we begin digging around the records, there are some important underpinning ideas to this research. Firstly, it’s important that we treat the recordings as the primary text, and by doing so we acknowledge the sonic elements as being intrinsic to the music’s meaning, as much as melody, lyric, harmony and arrangement.

Semiology is a useful methodology for this kind of thinking. Adapted from the study of linguistics, it has been adopted by popular music analysts such as Phil Tagg (1982, 1999, 2012), Peter Dunbar-Hall (1991) and Dave Machin (2010). It looks for signs/signifiers that carry meaning, references or associations. The concept of ‘meaning’ can be a problem, but we’ll come to that later.

Hauntology is a word popping up a lot in popular music analysis these days, and can be used to describe the ways in which a created object can be haunted by memories, ideas, snap-shots from different timelines/spaces. A crude analogy would be in how applying a sepia filter to a digital photograph can re-contextualise and inform the potential meanings of the photograph in question. In music, hauntological aspects could be particular recording and production techniques referencing a specific time and place (use of samples, sonic profiles associated with historical music scenes). With Bowie’s music, it could be the precise use of his voice, or a reference to his own myth/catalogue/sonic vernacular that haunts a piece of new music, a technique we see/hear a lot of in The Next Day (2013).

Slide 5:

For the purposes of this discussion, we will be considering 2 research questions:

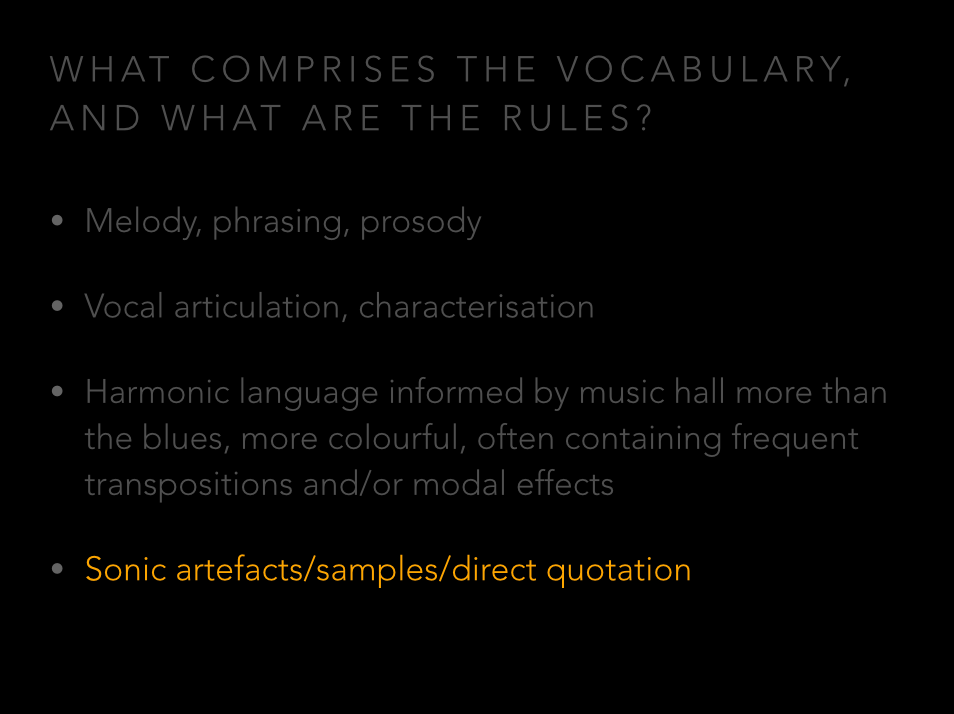

1. If Bowie has made a music and sound language, what comprises the vocabulary, and what are the rules?

2. If such a language can be recognised and understood by a listener, what potential is there for added meaning, added value, increased appreciation of a song?

Slide 6:

Looking at a few general areas of critical listening, due to time constraints we'll consider only a few examples from each category, starting with melody. Thinking about idiosyncratic approaches to melody, have a listen to the following 60 second montage, taking note of the trajectory of his voice, and the variances in intensity…

Click to play MELODIC EXAMPLE

Many songwriters might work a melodic phrase into an ‘arch’ shape, climbing up to a climactic point - in these examples Bowie seemingly throws his voice like a javelin, propelling it forward, hitting with intensity and then diminishing. If you listen to Ashes to Ashes you might notice that almost the entire song is sung in this way - even in the chorus when you think there is a climbing theme, there’s actually two and the other is constantly spiralling downward from a height. Certainly across the catalogue, Bowie's melody writing is often remarkable. Well worth further analysis.

The word prosody refers to the way in which words are set to melody, the way they work together to set up listener expectations, the way they scan. I’m going to ask you again to listen to a 60 second montage, to see if you can hear a trend here that transcends genre and style.

Click to play PROSODY EXAMPLE

We might even be able to filter these examples for lyrical theme, or even his voice type - whether he uses his full-throated vibrato, or a thinner more whiny voice. For this purpose I created a spreadsheet…

Slide 7:

This is a potentially larger area than I have time for in this presentation, but I’m going to flash some data in front of you and hopefully it will illustrate how consistent some combinations of vocalisation, theme, musical style and tonality are. I listened, and read other peoples’ analyses, and placed songs in categories - type of voice (Mockney, histrionic, detached, etc) alongside general lyric themes (madness, fame), tonality and musical style. Maybe I should have put in a column for his haircut? While this data set is a work in progress, already it reveals some interesting trends.

Voices vs Lyric themes: broadly speaking, the different voices of David Bowie sing about different topics, though there is a lot of overlap. It’s still interesting to pick at the details, the differences and commonalities of vocalisations when singing about two common lyrical themes ‘sex’ and ‘dystopia’.

Voices over years: You can see that his ‘detached’ voice doesn’t really come into use until the Berlin era, disappears after Scary Monsters (1980) and re-emerges in the late 80s with Tin Machine. His breathy ‘hushed’ voice (and the slightly odd ‘quasi-caribbean’) is exclusive to 83-93.

Modal efffects/tonality vs Lyric themes: it’s interesting that so many of his songs feature multiple transpositions to different key centres. This is certainly not songwriting written to the blues template, but a harmonic language more informed by music hall and soul music of the 60s. There are many songs that make use of the Mixolydian modal effect (the Major mode with the flattened VII chord), as well as a surprising repeated appearance of the Lydian modal effect, most notably in the narrative driven songs from 1. Outside.

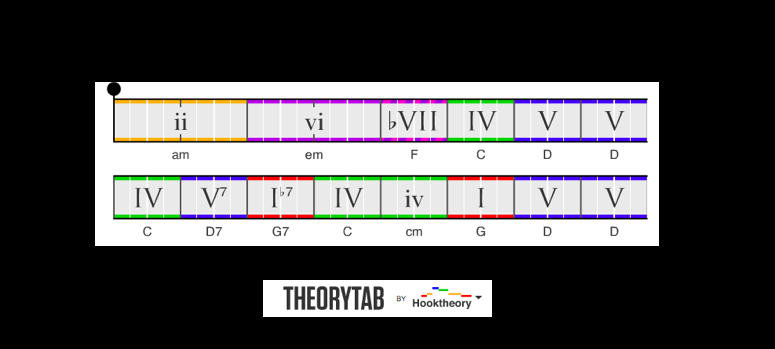

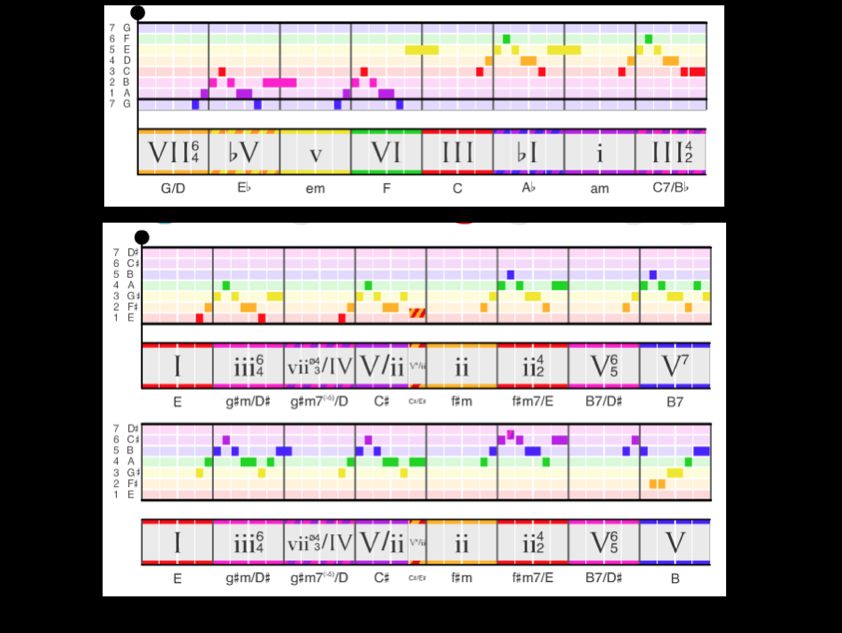

Slide 8:

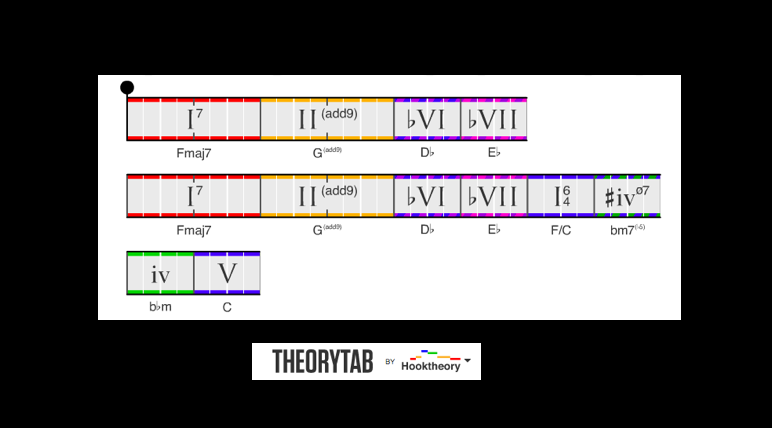

Bowie writes quite complex chord progressions, and his music is more harmonically diverse than your usual ‘3 chord wonder’ or blues based rock composition (it has been since the start, regardless of who he might be collaborating with). This becomes clear when you look at some charts.

These charts are from hooktheory.com, a great open/editable resource for analysing harmonic progressions in pop music. If you can’t recognise the song from the chart, it’s the bridge/B section from “Soul Love” (1972). It’s in G major and what you see here is a lovely, temporary excursion through related keys, the relative minor (Em), the subdominant (C), and back. Even on his most straight up and down rock n roll records, there's colour, movement, flourishes. People interested in digging deeper into this idea should check out/analyse the harmonies of Tin Machine's output, and wonder no more why their sound didn't quite fit with that of their hardcore/grunge/garage contemporaries.

This is the bridge of "Life On Mars" (1971). You can see some quite complex shifting through secondary dominants and other far flung places, setting a high standard for complexity in a pop music chord progression.

This is the opening harmony for ‘Where Are We Now” (2013)… it’s loaded with colour, straying from the basic diatonic language of most pop music that you might have heard in 2013.

Ok - but what could it mean? In setting up this consistency, it highlights moments of static non-harmony. When he keeps things colourless and/or unmoving, could it be for a reason/communicative purpose? (1. Outside Segues (1995), Sex & the Church (1993), Fame (1974))

The Lydian Modal Effect:

Click to play LYDIAN EXAMPLE

The Lydian modal effect is a melodic angle/chord progression that he’s been playing with in his songs since the mid-70s. It’s the distinctive tri-tone interval, the strange angle you hear in the opening notes of The Simpsons theme. Much of the 1. Outside theme/leitmotif is based around the lydian modal effect, and it can be heard again in one of his latest compositions “Sue (Or In A Season Of Crime)” (2014). When I first heard “Sue”, I recognised this familiar effect which caused me to immediately think about other examples, my mind making connections between different spaces/places in Bowie’s timeline, informing and contextualising my experience of the song - the song meaning for “Sue” that I was constructing for myself.

Slide 9:

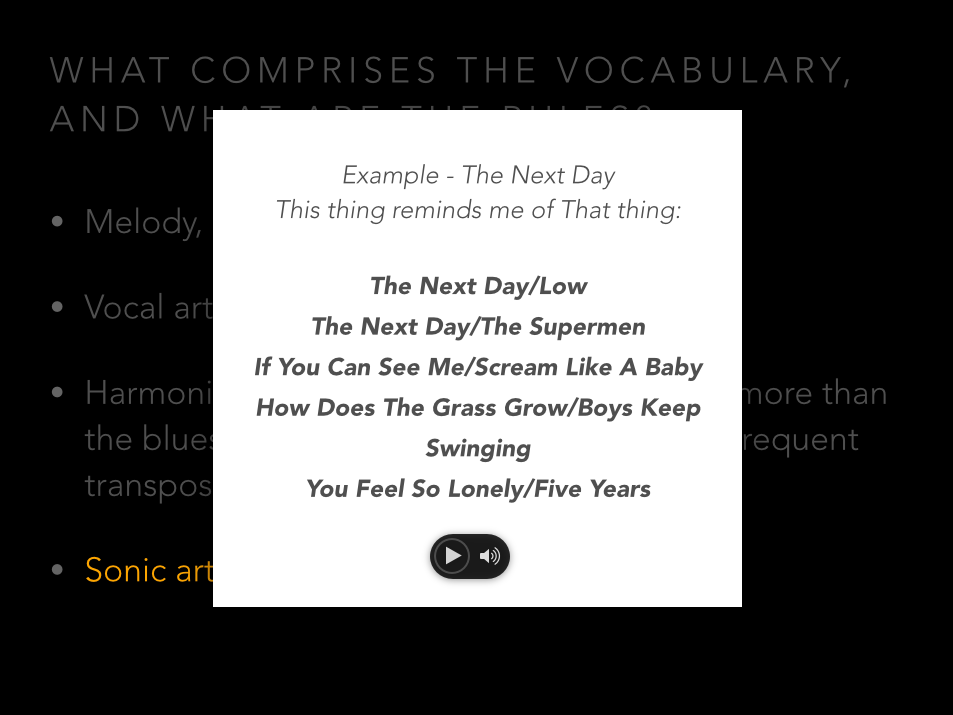

The Next Day is full of call-backs, apparitions from the past appearing momentarily. For the keen listener I’m sure these connections, (hauntings) can deepen the experience of the music, implying new layers of meaning, evoking memory and fusing it to the construction of new meaning (as the Lydian effect did for me in my reading of “Sue”).

This is the last listening example, we’ll play a game of This Thing Reminds Me Of That Thing. I’ll follow the new example from The Next Day with a connection that I hear from the past, starting with the first drum sound. Listen…

Click to play CALLBACKS EXAMPLE

Slide 10:

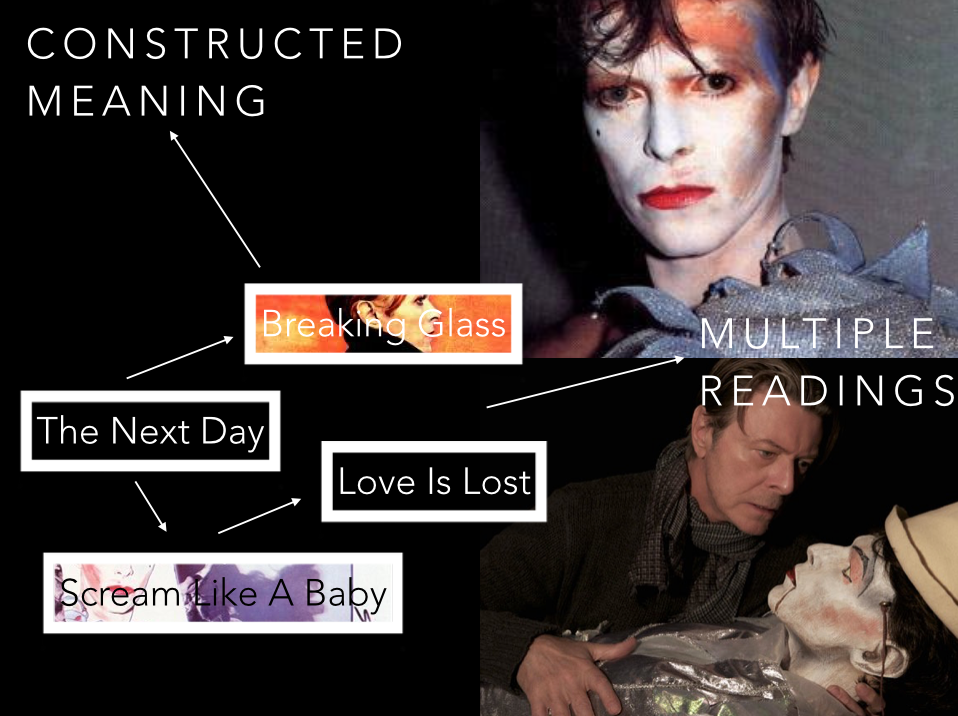

So what does it all mean? A more appropriate question is “what CAN it all mean"

Slide 11:

As you walked through the exhibition you might have come across a fantastic quote from David from 1995:

“All art is unstable. Its meaning is not necessarily that implied by the author. There is no authoritative voice. There are only multiple readings.”

And this is what we do, we make multiple readings. We can follow the signs and connect threads, we paint the details into the landscape. Further to this, we can contextualise the songs within the whole, interconnected body of work, one that is still growing.

Our close listening and analysis rewards us with personally constructed meanings that furnish pop songs with the stuff of multifaceted context and time-space connections, triggering nostalgia and memory to colour how we understand and feel in this present moment as we engage in the act of listening.

Slide 12:

The more you look, the more you might find.

/End.