Scary Monsters [Chapter 1]

In the summer of 2015 I sent a proposal off to the editors of the 33 1/3 series for a book about my favourite David Bowie album Scary Monsters and Super Creeps (1980). To my surprise and delight, out of the 606 proposals they received from their open call, I somehow made the shortlist of 85. In the end, my book idea was not chosen for publication (though I have to say the albums/authors that were chosen seem extremely worthy and I can't wait to read the new volumes).

Part of the proposal package included a draft introductory chapter, so I thought I would share that here just in case it is of interest to anyone. I realise that in the wake of the news of his death there has been a flood of amazing stories, blogs, think-pieces, memories and tributes - many people might be feeling some Bowie-death-fatigue setting in. I know I am. If that's the case I invite you to consider and celebrate the staggering body of work he has gifted us, as I ask you to focus on Scary Monsters and Super Creeps.

(click on the 'read more' link to see the chapter)

x LK

I Don't Want To Leave, Or Drift Away: the Lodger transition

On the 20th of May 1979, David Bowie was given two hours of airtime on BBC Radio 1 to spin some of his favourite records. Two days earlier, his album Lodger had been released, the lead single Boys Keep Swinging having been available for almost a month already. Lodger (originally titled Planned Accidents) was a pop music document borne of studio experimentation, the third of the so-called ‘Berlin Trilogy’, and of the three reputedly the most difficult and frustrating to realise. In Lodger the ambient-flavoured instrumental compositions that featured on side B of both Low and ‘Heroes’ (both 1977) were conspicuously absent. In their place stood more traditionally structured songs about seeing the world from different exotic perspectives, the lyric sheets containing more words than Low and ‘Heroes’ combined. Boys Keep Swinging epitomised the experimental and adventurous spirit of the album with its roughly played arrangement being the result of the studio players swapping their instruments, the song’s structure and chord progression a direct quotation of album opener Fantastic Voyage (certainly not the only example of experimental self-quotation on the album; Move On was written as a new melody on top of the reversed tape of All The Young Dudes. In music composition this kind of artistic cannibalism is not thought of as ‘cheating’, but merely being ‘economical’). Of course Bowie used his airtime on Radio 1 to promote his work from Lodger, but he also played other music that hinted towards an imminent shift: away from experimentation, improvisation and studio games, towards something leaner, tougher – punk, garage and new wave.

By the time of broadcast, Bowie had been the world’s citizen for about six years, leaving his native London in 1974 to base himself in America, Switzerland, Berlin, France and Switzerland once again. While Bowie soaked up his surroundings, metabolising these different environments into new musical directions like the proverbial fly floating in the carton of milk, younger music cultures heavily inspired by his influence were springing up in Manchester, London and New York. Bands like Devo and Talking Heads lined up to collaborate with the people that had worked with Bowie in the past (Devo’s first two studio albums produced by Brian Eno and Ken Scott, respectively). Fans of Ziggy and Low were now making their own music and alternative fashion scenes in England: the android androgyny and new romanticism of the Blitz Club kids in London, the Berlin/glam mashup of Gary Numan’s Tubeway Army, and the motorik-inspired Warsaw, who named their group after a track from Low, later changing it to Joy Division. In New York, the CBGBs-centric club scene was exploding with post-punk and new wave inspired by the Kraut-funk fusions of Bowie’s Berlin-era work, with bands like Blondie, Television, and again, Talking Heads enjoying huge critical and commercial success. After a decade of being on top of his game, Bowie now found himself in a strange new situation: he had become a patriarchal figure to a new generation, and there was a problem – this new generation was beating him down in the charts at his own game.

Perhaps some of the blame for this state of affairs lay with RCA, who really only wanted Bowie to turn in Young Americans 2 and give them another US number 1. Bowie had been growing frustrated with them for not properly promoting his more experimental work in the late 70s, and was unhappy with the stream of compilation packages they had released to cash in on the popularity of his earlier work. If RCA had worked harder for him, could Lodger have been a bigger hit?

Both Bowie and Tony Visconti expressed dissatisfaction with sound of Lodger’s mixes, completed in New York in early 1979. Visconti placed blame on the ‘less sophisticated’ studio equipment in the States for not being up to scratch1. Bowie owned up to being distracted by personal events during the finishing stages2 of the record and was reportedly even sheepish about delivering the final masters to RCA. Both of them complained about a ‘rushed’ final mixing process. It’s true that when you line up tracks from Lodger against the likes of 1979 chart-toppers such as Blondie’s Eat To The Beat and Tubeway Army’s Replicas, something seems amiss. Where Lodger’s mixes sound soupy and thin, Blondie’s sound confident, underlined, tough (despite being recorded in ‘less sophisticated’ NYC). Where the album’s arrangements sound flabby and indistinct, Tubeway Army’s textures are muscular, economical, and drip with a deliberate, stylised attitude (despite being completely written, performed and self-produced from scratch by Gary Numan).

Perhaps some of Lodger’s sonic flaccidity can be attributed to Eno’s desertion part-way through the process; after all, his magical moments were usually forged in the post- production stage of recording, when he was given time to treat, edit, splice, synthesise and reconfigure (that is to say ‘play with’) the already recorded materials. Perhaps it had something to do with the studio musicians growing tired of endless experimentation for its own sake. Guitarist and long-time Bowie collaborator Carlos Alomar later recalled feeling like his musical ability and intelligence were being insulted by a studio improvisation game involving Eno pointing randomly to chords written on a wall and being exhorted to just play them – and who could blame him?3 Perhaps the pioneering spirit on the Berlin Trilogy had, to borrow the words from Eno himself, ‘petered out’ after 19774. Melody Maker’s Jon Savage described the album as being “slightly faceless” and Rolling Stone likened it to “an act of passing time”. The New York Times praised it, calling it Bowie’s “most eloquent” outing in a long while, while Robert Christgau many years later would re-christen it “a certified nonclassic”. To this day Lodger remains an often unfairly dismissed album, certainly worthy of a reappraisal. Nevertheless, in 1979 the message was clear – the time was right for a reassessment. Sometimes you just feel that need to move on.

But move on to where? The signs pointed to New York, a place that Bowie later remarked had “a certain kind of energy”, where he “really felt the sidewalk”5. It was the place where the dominating sound of Blondie was born – their 1979 hit album Eat To The Beat was recorded at the newly built Power Station studios in Midtown, at West 53rd, an impressive specialist facility set up by audio whiz-kid Tony Bongiovi (Jon Bon Jovi’s cousin). While Visconti mixed Lodger at the Record Plant a dozen blocks down on West 44th, Bowie spent time hanging out with David Byrne, catching bands at CBGBs and concerts by contemporary New York composers Steve Reich and Philip Glass, performing art music with John Cale, and importantly, reconnecting with John and Yoko. Like the fly in the milk once again, David was soaking up New York.

“I think, a really despondent track... erm... he’d left his band, and he was doing his first solo album... I found it rivetingly depressing, I really enjoyed playing it to myself, it’s called ‘Remember’ by John Lennon.”

– Bowie/The David Bowie Star Special BBC Radio 1, 20th May 1979

In 1979, Bowie digs out one of his favourite records, John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band (1970) and appears to reconfigure its signature style (minimal, vulnerable, visceral) as a possible starting point for a new sound. During his 1978 tour, Bowie worked tentatively with guitarist Adrian Belew on a collection of Plastic Ono Band-inspired song ideas, but the project is left unfinished, any music evidence never seeing the light of day. He re-records his breakthrough hit Space Oddity (1969) in an arrangement that borrows so heavily from the Plastic Ono Band’s sonic profile it borders on pastiche. The new version of the song is performed on the Kenny Everett New Year’s Special for Thames Television – an intense, dramatic performance filmed on a set including the exploding kitchen and yellow padded cell that David Mallet would later use again in the iconic and sublime Ashes To Ashes video. The televised performance, along with new instrumental arrangement, suggested a very bleak update to Major Tom’s story since his launch into space a decade earlier. Plastic Ono Band is a record for exorcising demons to. It is the sound of facing the traumas of your past, made manifest in music.

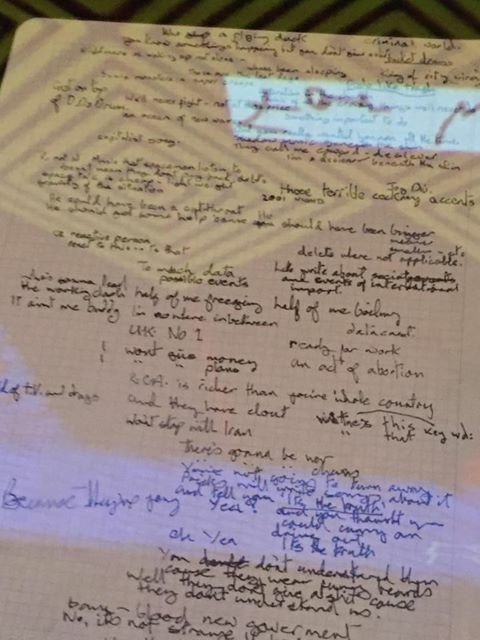

By the end of the 1970s, Bowie had a past, multiple pasts even, to face up to and make peace with. Later on in his career he would remark that Scary Monsters represented a process for “eradicating the feelings within myself that I was uncomfortable with. You have to accommodate your pasts within your person. You have to understand why you went through them... It’s very important to get into them and understand them. It helps you reflect on what you are now.”6 In trying to unpack who and what David Bowie is at the end of the 1970s, he looks back at his roots in 1950s pop music, his beginnings as a performer of mime, forgotten songs that he wrote as a teenager in which he imagined what it would feel like to be old and ‘tired of life’. He plays Ronnie Spector and Little Richard records to his Radio 1 listeners, along with some classical music – a movement from Edward Elgar’s Nursery Suite about a ‘sad doll’. He imagines re-enacting the scene where pierrot walks alongside the old lady on the back cover of Space Oddity. He resurrects Major Tom and officially grants him dark closure. Thinking about what his new album could be, on a scribbled sheet of notepaper7 he writes, “space talk is cheap”, “an ocean of new waves”, “UK No. 1 / ready for work / an act of abortion” and “scary monsters and super creeps”.

Bowie’s divorce was imminent, and throughout 1979 its lengthy and expensive proceedings were frustrating and distracting to the point of hindering his work in putting the finishing touches on Lodger. Soon he would be a single dad, the sole carer for his son Joe (a nickname; Duncan Jones is now widely known as the acclaimed film director of Moon, Source Code and the upcoming World Of Warcraft). He was also nearing the end of his unhappy contract with RCA, the record company that he had been with since Hunky Dory (1971). After failing to convince them to count the double live album Stage (1978) as two recordings worth of contractual obligation paid, after Lodger he only needed to deliver one more studio album to be free. Other binding agreements with ex-manager Tony DeFries were due to expire in 1982, after which time Bowie could for the first time control his own career and fortune. The possibilities offered by the arrival of freedom were tantalisingly close.

“All clear 1980. Personal – eyes only.” – Thoughts On The New Decade, Bowie, Melody Maker, 1st January 1980.

On the 1st of January 1980, six days before he turns 33, Bowie publishes a list of his “Thoughts On The New Decade” in Melody Maker’s new year special. In it he sets the tone for what will follow: “tragedy converted into comedy, indifference”, “to win a revolution by ignoring everything else out of existence”, foreshadowing some of the lyrical cynicisms that pop up on Scary Monsters, possibly even alluding to a grander plan for setting greater emotional distance between himself and his work during the rest of the 80s. He headlines the list with a mission statement (and shameless plug for his next promo compilation All Clear (1980), which featured a song from each album so far released on RCA). “All clear 1980. Personal – eyes only.” There was work to do yet, some personal business to take care of.

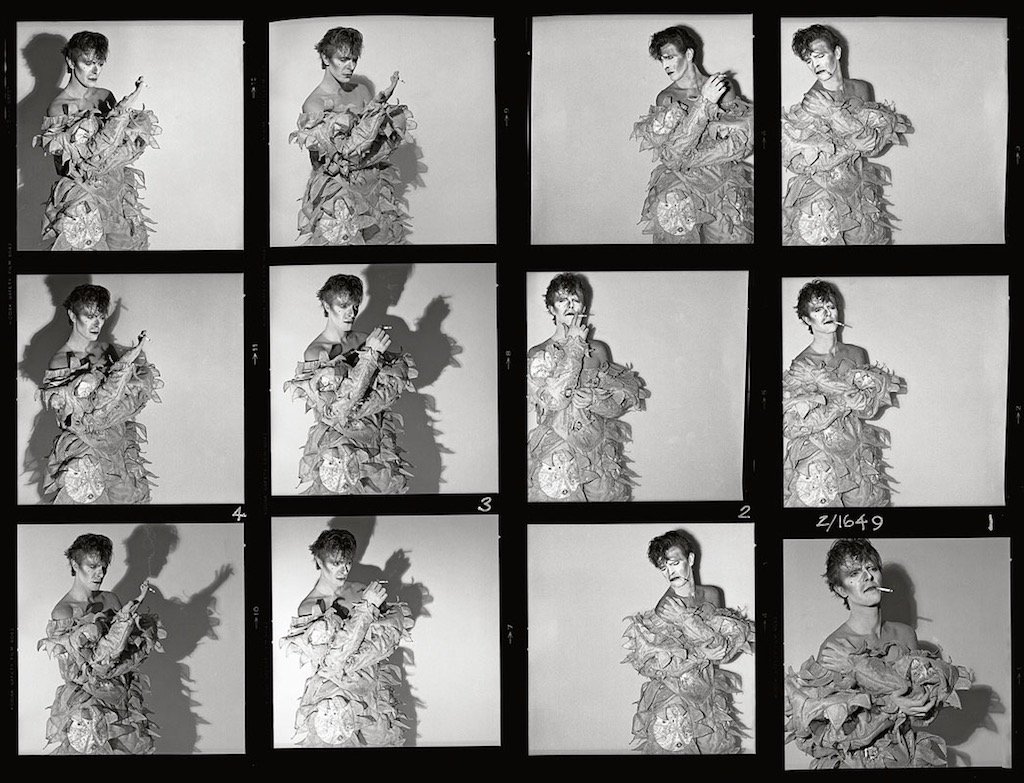

On the 5th of January Bowie appears on Saturday Night Live, seemingly cracking on with his stated goal of converting tragedy into comedy with performances of new and old songs (The Man Who Sold The World, TVC15 and Boys Keep Swinging), incorporating a bizarre array of moulded costume props, drag costumes, surreal camera tricks and puppets. His backing band features Blondie keyboardist Jimmy Destri, drag artist Joey Arias and German performance artist Klaus Nomi on backing vocals. Here we can witness Bowie in the very act of synthesising his influences and mythology with his new surroundings, distancing and reconfiguring elements of his past to express his thoughts and feelings in the present.

Five weeks later a trusty team of old friends and collaborators would assemble in New York at Power Station studios, including the core rhythm section from the Berlin Trilogy albums: Carlos Alomar (guitar), George Murray (bass) and Dennis Davis (drums and percussion). Tony Visconti would once again sit in the producer’s chair in what would become his last collaboration with Bowie for 21 years. Guitarist Robert Fripp, whose transcendent creativity so beautifully marked the sonic landscape of ‘Heroes’ returned once more to lend his distinctive sound to the sessions, alongside Chuck Hammer on guitar-synthesiser and Roy Bittan, taking a break from Springsteen duty, on piano. This would be the scene and cast of characters with whom Bowie and Visconti could finally realise their own Sgt. Pepper, their career-defining masterpiece.

How on earth do you begin? With a primal scream...

*************

1 “My only regret is that we went to New York to finish this album, and it suffered at the mixing stage because New York studios simply were not as versatile or well-equipped as their European counterparts in those days." – Tony Visconti, quoted in Nicholas Pegg's Complete Bowie (2011)

2 " I think Tony and I would both agree that we didn’t take enough care mixing. This had a lot to do with my being distracted by personal events in my life and I think Tony lost heart a little because it never came together as easily as both Low and Heroes had." – David Bowie, interview with UNCUT (2001)

3 In recalling the 'chord experiment’ conducted by Brian Eno using a blackboard and pointer, "I finally had to say, this is bullshit, this sucks" – Carlos Alomar, paraphrased in Ben Graham's piece 30 Years On: David Bowie s Lodger Comes In From The Cold, The Quietus (2009) (http:// thequietus.com/articles/03161-30-years-on-david-bowie-s-lodger-comes-in-from-the-cold)

4 Ian Gittens (2007). “Art Decade”, MOJO 60 Years of Bowie: pp. 70-73

5 Interview from Such A Perfect Day, Mike Jollett, July/August 2003, Filter (US)

6 Quote appears in Nicholas Pegg's The Complete David Bowie (2011)

7 These notes are featured as part of the touring V&A exhibit David Bowie is - V&A (2013-15)

and some cheeky shots of those scribbled notes (from the V&A David Bowie Is Exhibition). Here's my best attempt at a transcription. I regret nothing.